Summary

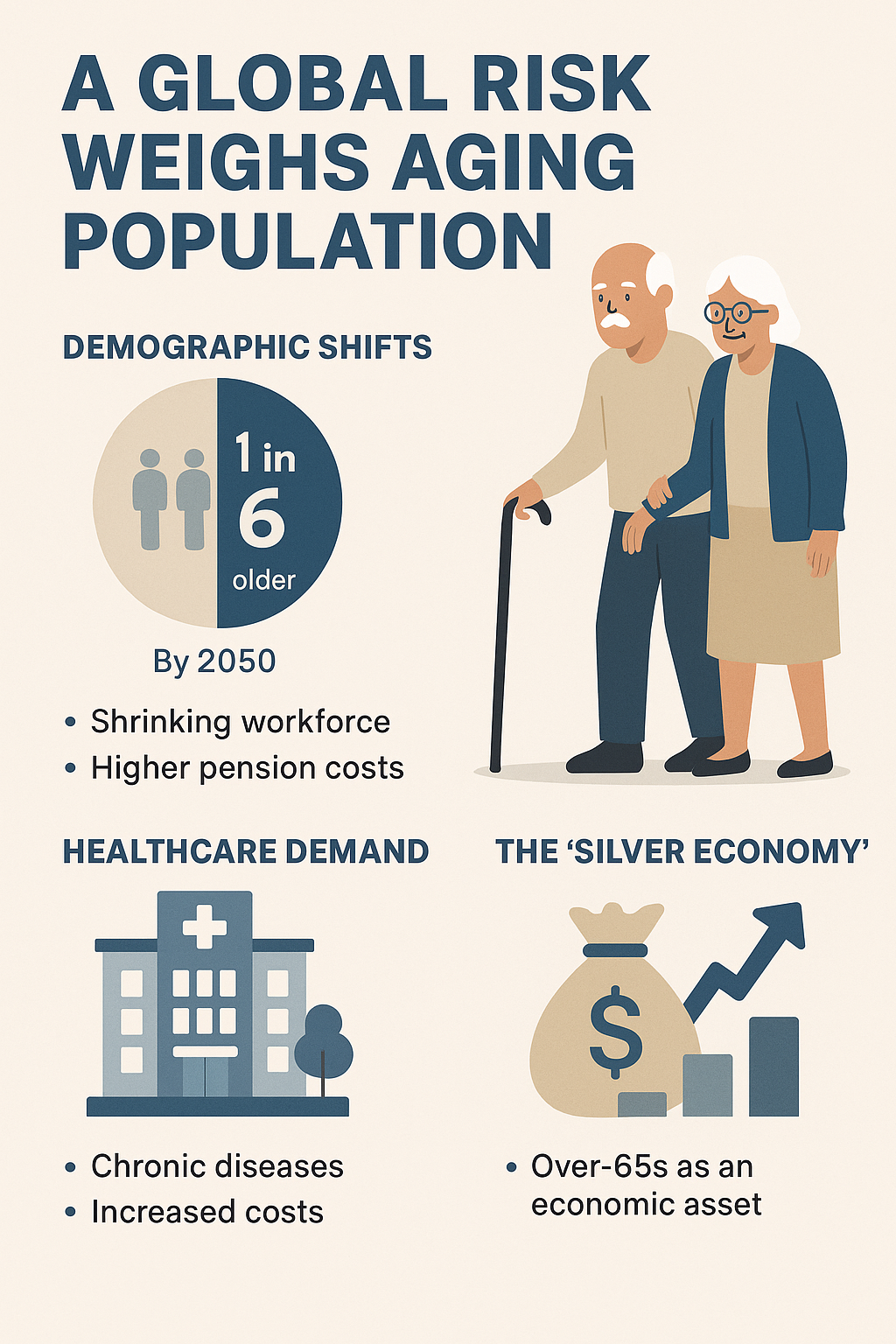

The world is experiencing an unprecedented demographic transformation that poses one of the most significant global risks of the 21st century . By 2030, one in six people worldwide will be aged 60 years or over, with the elderly population projected to increase from 1.1 billion in 2023 to 1.4 billion by 2030 . This demographic shift represents a fundamental challenge that could reduce global GDP growth by 0.5-1.0 percentage points annually—an economic impact greater than climate change . The aging population crisis extends far beyond simple demographics, threatening to destabilize social security systems, overwhelm healthcare infrastructure, and fundamentally alter the global economic landscape.

The Scale of Global Population Aging

Current Demographics and Projections

Global life expectancy has reached 73.3 years in 2024, representing an increase of 8.4 years since 1995 . The number of people aged 65 and older worldwide is projected to more than double, rising from 761 million in 2021 to 1.6 billion in 2050 . The global share of people aged 65 and over has nearly doubled from 5.5% in 1974 to 10.3% in 2024, with projections indicating this figure will reach 20.7% by 2074 .

The demographic transformation is accelerating at an alarming pace. The number of people aged 80 and older is expected to triple between 2020 and 2050, reaching 426 million . By 2100, the global share of the old-age population will rise from 4% in 1800 to 24%, with East Asia and Europe leading this trend . These statistics represent not merely population changes but fundamental shifts in the structure of human civilization.

Regional Variations and Super-Aging Societies

The World Health Organization defines “super-aging” societies as countries with more than 20% of their population over age 65 . Currently, over 40 countries have achieved super-aged status, with Monaco leading at 36% of its population being over 65 . Japan remains the world’s oldest society with 28% of its population aged 65 or older, followed by Italy at 23% .

Asia and Europe are home to the world’s oldest populations, with Eastern and South-Eastern Asia housing 261 million people aged 65 or over in 2019, followed by Europe and Northern America with 200 million . However, the fastest growth in elderly populations is projected for Northern Africa, Western Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa over the next three decades . China faces a particularly dramatic transformation, with its old-age dependency ratio projected to be 1.7 times the global average by 2050 .

Economic Implications and Risks

Labor Force Decline and Productivity Challenges

The economic consequences of population aging are profound and multifaceted. An aging population means fewer working-age people participating in the economy, leading to supply shortages of qualified workers and making it difficult for businesses to fill in-demand roles . This demographic shift creates adverse consequences including declining productivity, higher labor costs, delayed business expansion, and reduced international competitiveness .

Research demonstrates that population aging proxied by old-age population share negatively affects economic growth, with particularly pronounced effects at higher aging thresholds . At the 20% level of old-age population, a one-percentage point increase decreases the five-year economic growth rate by 3.5 percentage points . The relationship between labor productivity and age follows a reverse U-shaped pattern, with workers achieving peak productivity around age 50 before experiencing decline .

Macroeconomic Disruptions

The change in age structure impacts key macroeconomic variables including savings and investment ratios, inflation rates, and overall economic productivity . Young economies such as emerging Asia and Africa may benefit from demographic dividends, but demographic change does not improve per capita GDP . In aging economies like Japan and Europe, population aging decreases real interest rates, though this effect is offset by rising interest rates in younger economies, leading to substantial capital flows from aging to less aging economies .

Dependency Ratio Crisis

The old-age dependency ratio measures the number of retirees relative to the working-age population, and this rising ratio threatens the financial balance of social security systems . Traditional pay-as-you-go pension schemes, which rely on current workers’ contributions to fund retirees’ benefits, are particularly vulnerable to demographic shifts . The dependency ratio crisis means that the financial burden on the working-age population to support retirees is increasing dramatically, raising concerns about intergenerational equity and economic stability .

Healthcare and Social Security Burden

Escalating Healthcare Costs

Population aging leads to inevitable increases in social security payments, particularly for medical care and long-term care . In Japan, for example, annual medical costs in FY2020 were ¥340,000 per capita for the general population but ¥1 million per elderly person . The relationship between aging and healthcare costs is complex and multifaceted, with chronic condition management, long-term care services, advanced medical technology, and pharmaceutical expenses all contributing to rising costs .

Research from Germany shows healthcare expenditures increased by 54.2% from 2004 to 2015, with demographic change accounting for 17.3% of this increase . In South Africa, studies demonstrate a positive relationship between healthcare expenditure and the old-age dependency ratio, indicating that countries must account for aging populations when designing healthcare policies .

Pension System Sustainability

The demographic shift toward aging populations places unprecedented financial strain on pension systems worldwide . Traditional pension schemes designed for different demographic distributions, anchored by plentiful young workers and relatively few retirees, face the risk of becoming unsustainable . In Japan, the total amount of public pension payments reached ¥56 trillion in FY2021, with pensions and medical expenses alone accounting for 89% of social security spending .

Healthcare Access and Quality Challenges

In the United States, 77% of seniors report concern that rising healthcare costs will result in significant and lasting damage to the economy . The economic fragility of older adults has been exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, rising inflation, and increasing economic inequality, reducing the purchasing power of fixed incomes . Current cohorts of adults at or nearing retirement age face higher levels of secured and unsecured debt burden compared to prior cohorts, creating “financial fragility” that may result in older people foregoing proper nutrition, medical care, and needed medications .

Social and Political Consequences

Intergenerational Tensions

The aging population crisis creates significant intergenerational tensions as smaller working-age populations bear increasing responsibility for supporting growing elderly populations . Economic and other resources must be reallocated from research and development, educational systems, and technological advancements to caring for the elderly, funding senior healthcare, and maintaining pension payouts . This reallocation may hurt economic growth and overall quality of life if governments divert public spending from education and infrastructure investment to finance programs for the elderly .

Political and Governance Challenges

Population aging presents challenges to fiscal and macroeconomic stability through increased government spending on pension, healthcare, and social benefits programs . Many nations face already-high public spending that limits fiscal possibilities for increased aging-related spending in the long run . The unprecedented nature of this demographic crisis means that societies cannot rely on earlier historical episodes for guidance on how this upheaval will unfold .

Policy Responses and Mitigation Strategies

Comprehensive Policy Frameworks

Governments worldwide are implementing various strategies to address aging population challenges. Japan’s “Guideline of Measures for Ageing Society” aims to create an “Age-free society” where people of all ages can utilize their motivation and abilities . The framework recognizes that older people are “getting younger in situation of physical age” and emphasizes developing social environments where motivated older people can demonstrate their abilities .

Key policy strategies include: developing long-term visions, creating measurement indicators, promoting health for all ages, increasing older people’s engagement in labor markets and social activities, providing affordable housing in accessible environments, and redesigning urban areas to increase attractiveness and well-being .

Labor Market and Economic Interventions

Encouraging older workers to remain longer in the labor force is often cited as the most viable solution to fiscal pressures and macroeconomic challenges . Policy instruments vary by demographic transition phase, including workforce development and vocational training for mid-transition countries, and aging and pension reforms with gradual retirement age increases for late-transition societies .

Economic strategies encompass pension reform to ensure sustainability and reduce burden on younger generations, labor market adjustments through training programs and flexible work arrangements, and healthcare strategies focusing on preventive care and age-friendly services .

Healthcare System Adaptations

Healthcare policy responses include expanding universal health coverage to protect families from catastrophic health expenditures, investing in rural health clinics and vaccine logistics to reduce infant mortality, and implementing community-based long-term care with telemedicine integration . The focus on preventive care can help reduce the incidence of age-related diseases and promote healthy aging through health education, screening programs, and vaccination campaigns .

Future Outlook and Recommendations

Long-term Demographic Projections

The world population is expected to peak at around 10.3 billion in the mid-2080s before declining to 10.2 billion in 2100 . By 2100, East Asia will have the highest share of old-age population at 45%, followed by Europe and Latin America at around 33% . Meanwhile, Sub-Saharan Africa will lag with just 14% elderly population, less than one-third of East Asia’s share .

Strategic Recommendations

Addressing the global aging crisis requires coordinated international action encompassing multiple policy domains. Countries must implement comprehensive demographic transition strategies that balance economic growth with sustainability concerns . Essential interventions include pension system reforms, healthcare infrastructure development, labor market flexibility enhancements, and social policies promoting age inclusivity while combating isolation .

The demographic dividend—accelerated economic growth due to increasing working-age population share—provides temporary opportunities for countries early in the aging process, but maximizing these benefits requires evidence-based policies tailored to specific population needs .

Conclusion

The global aging population represents an unprecedented challenge that will fundamentally reshape societies, economies, and political systems worldwide. With the elderly population set to more than double by 2050 and the potential for GDP growth reduction exceeding climate change impacts, this demographic transformation demands immediate and comprehensive policy responses. While the crisis presents significant risks including labor shortages, healthcare system strain, and intergenerational tensions, proactive policy interventions focusing on extended working lives, healthcare system adaptations, and social security reforms can help mitigate these challenges. The success of these interventions will determine whether societies can adapt to demographic reality or face economic and social destabilization in the coming decades.

Find Trusted Cardiac Hospitals

Compare heart hospitals by city and services — all in one place.

Explore Hospitals

This article offers a thoughtful and well‑rounded look at the global aging population challenge — I really appreciated how it breaks down the socioeconomic implications alongside health and care issues, making it clear this isn’t just a demographic fact but something that affects systems and families worldwide. The way it connects data with real‑world impacts helps readers truly understand why planning and policy matter so much as populations shift. A very insightful and timely read!